IAHPC Traveling Fellowship - India

Vivek Khemka , MD (March 2005)

Background

I am a board certified Internist and Geriatrician currently completing my one-year fellowship in pain and palliative medicine at Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx in New York. As part of my fellowship I had the option to travel anywhere in the world for four weeks as an elective to learn or teach palliative medicine. I chose to travel to India where I originate from to see the progress made in palliative care and to conduct workshops for physicians as an introduction and basic training in palliative care.

There was no palliative care training available in Chennai when I went to medical school over a decade ago, as well as later when I worked there. This visit was designed to look at the present state of palliative care and to develop ways of improving and strengthening existing services through collaboration, and also to look at possibly integrating palliative care education into post graduate training.

India is home to almost a fifth of the world’s people. There is an estimate of over a million and a half people diagnosed with cancer every year and several millions living with HIV; most of whom are diagnosed in the late stages. The ageing population is also growing and they present with several other chronic diseases. The medical curriculum lacks geriatric education. In the past decade, there has been rapid economic progress and improvements in health care in both the government and private sectors. Despite this there are still hundreds of millions of people lacking access to basic health care and because of this, cancer, HIV and many other diseases are diagnosed in the very late stages of the illness. Even among those with access to care, only a tiny fraction have access to palliative care and even fewer have access to opioids for pain relief and end of life care. This is despite the fact that India is the largest legal producer of morphine in the world. As in most parts of the world, there is a paucity of palliative care training in medical and nursing schools with the major training centers concentrated in the Southern state of Kerala. Due to the involvement of the Indian Association of Palliative Care, there is a gradual improvement in palliative care education in some urban areas. There is a basic six-week course on palliative care at the Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences (AIMS) and few other places in Kerala. AIMS also has an advanced two year post graduate training program.

My visit to India was planned to provide a workshop on basic training based upon the EPEC (Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care) curriculum, which has been a very effective program here in the US and has also been used in a few other countries. I chose to use the EPEC curriculum since I am an EPEC trainer and also since it is a very simple and flexible model for teaching palliative care. I had planned, and was able, to provide copies of the EPEC curriculum to all participants because of the grant from the IAHPC.

I had worked at Sundaram Medical Foundation in Chennai before I left the country and was familiar with the practice environment; it seemed to be a good place for me to start. My host Dr. Arjun Rajagopalan, Chief of Medical Staff, has been very supportive of furthering palliative medicine education and extended an invitation to teach there. I did workshops at Rajiv Gandhi Cancer Institute in Delhi, the capital of India, Bhagwan Mahaveer Cancer Institute in Jaipur, the capital of the state of Rajasthan, at Sundaram Medical Foundation in Chennai and also at the Barnard Institute of Radiology and Oncology at the Madras Medical College (now known as Chennai Medical College) in Chennai which is one of the oldest medical schools in the country.

Activities

The day after I reached Chennai I went to the Sundaram Medical Foundation to meet Dr. Arjun Rajagopalan and discuss the details and arrangements for the workshop. Two days later I left for Kochi , in Kerala, to meet Dr. M. R. Rajagopal at Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences and to spend time learning from him about the state of palliative care in India and about his program - he is one of the first people to specialize in palliative medicine in India . He heads the departments of anesthesia and pain palliative medicine and directs the only post graduate diploma training program in pain and palliative medicine in the country. While in Kerala, I also had the opportunity to present several modules from the EPEC curriculum that I had modified for the Indian setting.

Dr. Rajagopal and I also had an opportunity to make a presentations to the medical board of the institution on the issues of non-beneficial treatments and the withholding/withdrawing of artificial ventilation and other life support measures at end-of-life when patients did not want them, or when it was obvious they were futile - there are presently no clear guidelines in India on these issues. We had discussions on the ethical and legal basis on how these issues were approached in the US and other countries. The possibility of multiple medical societies coming up with a joint statement on this issue was also explored.

Non-beneficial treatments and withholding/withdrawing treatments have been an issue the Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine (ISCCM) has looked at in great detail from both a medical and ethical perspective and had recently drafted a set of guidelines which they had offered for comment. In the absence of clear detailed legal guidelines, this is the best set of guidelines available to physicians in India . Another barrier we discussed was the distinction between physician assisted suicide and euthanasia which are not legal in India . We also discussed the role of palliative care in the intensive care units when the patients’ condition worsened despite the best available treatments, and in accordance with their wishes.

I then spent two days at Rajiv Gandhi Cancer Institute in Delhi . I conducted an interactive workshop over two days, which was well received by the faculty and staff. I then went to Jaipur where I visited Bhagwan Mahaveer Cancer Institute. I attended a workshop on interventional and non-interventional pain. I conducted a two day interactive workshop on the complete EPEC curriculum. The most interesting parts of the workshop were the legal issues, which were presented by Dr Kabra, a surgeon and a lawyer, who is also associated with the Avedna hospice in Jaipur. Dr Rakesh Gupta, surgical oncologist and Oxford trained in palliative medicine and founder of Rajasthan Cancer Foundation, made an excellent presentation on communicating bad news to patients and families and the importance of involving patients in the decision making process. In most non-western cultures including India , there has always been the notion that telling patients the diagnosis will harm them and families do not want their loved ones to know they have cancer. We discussed this since in reality most patients already know their diagnosis either form reading their multiple test results, which they have easy access to, or from speaking with other patients during treatment. Most physicians felt it was better to talk to the patient about their diagnosis and involve them in the treatment plan rather than the patient finding out on their own.

I returned to Chennai and networked with some community and hospital based physicians and had the opportunity to learn how they approached palliative care issues in the environment of restricted access to opioids and the lack of experience in using them. I conducted a two-day workshop at Sundaram Medical Foundation using the EPEC curriculum - it was attended by physicians and residents from the hospital as well as from the community. Drs. Rajagopal and Gayatri Palat traveled from Kochi to study the effectiveness of the EPEC curriculum as a teaching tool in the Indian setting. Dr. Reena George, Oncologist and Head of Palliative Medicine at Christian Medical College , Vellore made a presentation on common physical symptoms and their management in patients with advanced disease and at end-of-life. We again discussed the legal and ethical issues and the possibility of preparing a joint position statement on treatments at end-of-life based upon the ISCCM guidelines. The workshop was also covered in a leading daily newspaper.

The next day I visited the Barnard Institute of Radiology and Oncology at Madras Medical College . I had opportunity to make presentations on communicating bad news and on legal issues; both were well received and followed by detailed discussions on various aspects of palliative medicine and the role of oncologists and other physicians in continuing to care for the patients even in advanced disease.

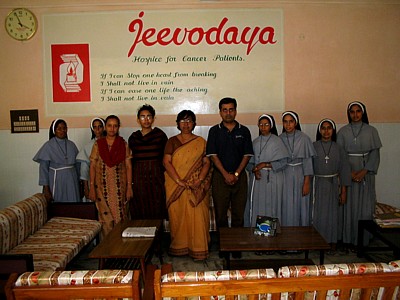

I then visited Jeevodaya Hospice for cancer patients, which is run by missionary nuns who are also trained in nursing. They provide charitable in-patient palliative care to patients with advanced cancer. I was very moved by their dedication and involvement in providing care when others were unable to do so. It gave me the feeling that people still care for others; I hope it is not lost in our society.

I also visited Dean Foundation in Chennai, which is a charitable organization run by Deepa Muthiah providing palliative care to those who are not able to afford it. I learnt about their extensive use oral morphine and their use in palliative care of complementary and alternative medicine which is more acceptable to many of their patients.

Observations:

- There is a lack of awareness about palliative care among people, physicians and healthcare workers.

- There is a lack of access to palliative care.

- Most palliative care centers were concentrated in one state in India . Kerala has more palliative care clinics than the rest of the country put together.

- There is a lack of standardized training programs and only one post-graduate training program in palliative care in the entire country.

- Restrictive regulations and a lack of opioid availability contribute to the already poor availability of palliative care.

- The focus on a single drug Morphine as the solution to all palliative care needs has in many ways prevented further developments and resulted in the lack of other cost effective potent opioids, especially methadone, from being used. Some gains have been made in opioid availability, but it is still a tiny fraction of the need.

- There is a lack of clear guidelines for palliative and end-of-life care.

- There is a willingness among a few physicians and certain medical societies and organizations to get involved in improving the situation despite the slow process by the government.

- Most palliative care programs are charitable and focus on the poor. People who can afford to pay for services have little access to them. Hospitals and physicians do not see palliative care as a revenue-generating specialty and therefore are not interested in this area.

- Existing Palliative care programs are struggling for resources and funds to survive.

Accomplishments in collaboration with the institutions in India :

- Distinction between euthanasia, physician assisted suicide and withholding/withdrawal of treatments was made clear during the workshops.

- Legal and ethical issues in palliative and end-of-life care were discussed in detail and participants gained an insight into the various aspects of palliative care.

- A collaborative process was initiated along with the EPEC project for adaptation of the EPEC curriculum as a teaching tool in India and for future workshops. The feasibility is being studied and should be underway within this year.

- A process for inter-society collaboration for the study and issuance of a joint statement regarding ethical and medical issues in end-of-life care was initiated.

- Awareness was created about the mechanism established by the IAHPC and AIMS whereby physicians may obtain formal training in palliative care at AIMS under an IAHPC scholarship program.

- I provided several books on palliative care to each of the institutions I visited during my trip to India .

Future Follow-up Plans:

Efforts are underway to identify a core group of physicians and other experts who would be willing to pursue a long-term plan through regular visits to centers in India . The aim of this group would be to start programs that are able to achieve self-sustainability within a reasonable time.

I hope to be able to visit India again within the year to follow up on this plan. In the meantime, technology and the Internet, have enabled us to keep in touch very cost-effectively.

A few weak opioids are available; however in the class of strong opioids, only the cheapest (morphine) and the most expensive (fentanyl) are currently available.

I hope to work collaboratively with the palliative care physicians and policymakers in India to make opioids, other than morphine, more available.

This is a shortened version of Dr. Khemka’s report; the complete report may be read on our website at URL:

http://www.hospicecare.com/travelfellow/tf2005/india.htm

|